The Intricate Dance Between Money and the Human Mind

Money is one of humanity’s most powerful creations. It transcends its physical form as coins, paper, or digital digits to become a cornerstone of human civilization. Yet, despite its omnipresence in our lives, money remains an enigma—a tool that shapes behavior, emotions, and even cognitive processes in ways we are only beginning to fully understand. At its core, money is not just a medium of exchange; it is a psychological construct that influences how we think, feel, and interact with the world around us. This article delves into the fascinating relationship between money and the human mind, exploring unique insights from psychology, neuroscience, behavioral economics, and philosophy.

The Evolutionary Roots of Money: A Psychological Perspective

To comprehend why money has such profound effects on the human psyche, we must first consider its evolutionary origins. Before money existed, humans relied on bartering systems where goods were exchanged directly for other goods. However, this system had limitations—it required a “double coincidence of wants,” meaning both parties needed something the other possessed. Money emerged as a solution to these inefficiencies, serving as a universal store of value and facilitating trade.

From an evolutionary standpoint, money taps into fundamental survival instincts. Early humans sought resources like food, shelter, and tools to ensure their survival. Over time, these tangible assets evolved into abstract representations of wealth—money. The brain adapted accordingly, associating money with security, status, and power. Neuroscientists have discovered that handling money activates regions of the brain linked to reward processing, such as the ventral striatum and prefrontal cortex. These areas light up when people anticipate financial gain, suggesting that money triggers primal pleasure circuits akin to those activated by food or social connection.

Interestingly, research shows that merely thinking about money can alter behavior. Kathleen Vohs, a psychologist at the University of Minnesota, conducted experiments demonstrating that exposure to money-related concepts makes individuals more self-reliant but also less empathetic. Participants who handled money before completing tasks showed increased perseverance in solving problems independently but exhibited reduced willingness to help others. This duality underscores the dual nature of money: while it empowers individuals, it can simultaneously erode communal bonds.

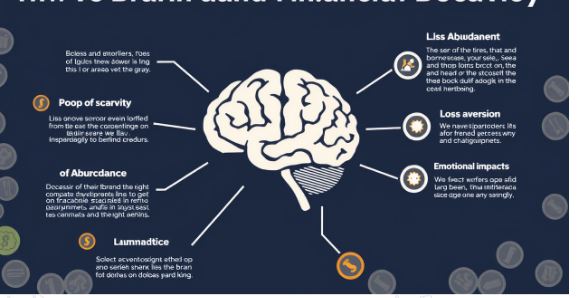

The Psychology of Scarcity vs. Abundance

One of the most intriguing aspects of money’s impact on the mind is its ability to shape perception based on scarcity or abundance. When resources are scarce, the brain enters what Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir call a “scarcity mindset.” In their book Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, they argue that scarcity captures attention, narrowing focus to immediate needs at the expense of long-term planning. For example, someone struggling financially may obsess over paying bills today without considering retirement savings tomorrow.

This tunnel vision stems from the brain’s limited cognitive bandwidth. Studies show that financial stress impairs executive functions such as decision-making, impulse control, and problem-solving. Conversely, experiencing abundance fosters creativity, generosity, and forward-thinking. People with ample resources tend to take risks, invest in opportunities, and prioritize experiences over material possessions. Understanding this dichotomy highlights the importance of addressing systemic inequalities—not only for economic reasons but also for mental well-being.

Moreover, the perception of scarcity versus abundance isn’t always tied to actual wealth. Two people earning identical incomes might perceive their situations differently due to upbringing, cultural norms, or personal expectations. This subjective experience of wealth further complicates the relationship between money and the mind, illustrating that financial health is as much about mindset as it is about numbers.

The Dark Side of Wealth: How Money Corrupts

While money provides freedom and opportunity, excessive wealth can distort moral judgment and interpersonal relationships. Psychologists refer to this phenomenon as the “corrupting influence of wealth.” Research indicates that affluent individuals often exhibit lower levels of empathy and compassion compared to those with fewer resources. One study found that drivers of luxury cars were significantly less likely to stop for pedestrians at crosswalks than drivers of economy vehicles.

Why does wealth lead to diminished prosocial behavior? The answer lies in the concept of social distance. As income increases, individuals may begin to see themselves as separate from—or superior to—the rest of society. This detachment diminishes feelings of responsibility toward collective welfare. Additionally, wealthy individuals often attribute their success to personal merit rather than external factors like luck or privilege, fostering a sense of entitlement.

Another concerning trend among the wealthy is the pursuit of extrinsic goals—such as fame, status, and material possessions—at the expense of intrinsic values like relationships, personal growth, and community involvement. Tim Kasser, a psychologist known for his work on materialism, argues that prioritizing extrinsic goals leads to decreased happiness and increased anxiety. Ironically, the relentless pursuit of wealth can leave individuals feeling emptier than ever.

Neuroscience Meets Finance: Decoding Monetary Decision-Making

Advances in neuroscience have shed light on how the brain processes monetary decisions. Functional MRI scans reveal that different parts of the brain activate depending on whether a choice involves gains or losses. The prospect of winning money stimulates the nucleus accumbens, a region associated with pleasure and motivation. Conversely, potential losses engage the amygdala, which governs fear and risk aversion.

These neural dynamics explain common biases in financial decision-making. Loss aversion, for instance, describes the tendency to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains. This bias explains why investors cling to underperforming stocks instead of cutting their losses—a phenomenon known as the “sunk cost fallacy.” Similarly, the endowment effect causes people to overvalue items simply because they own them, leading to irrational attachment to possessions.

Understanding these cognitive quirks is crucial for improving financial literacy. By recognizing the psychological pitfalls inherent in monetary decisions, individuals can adopt strategies to mitigate their impact. For example, setting clear investment goals, automating savings, and seeking professional advice can counteract impulsive behaviors driven by emotion.

Cultural Perspectives on Money: Beyond Individual Psychology

While much of the discussion so far has focused on individual psychology, it’s essential to acknowledge the role of culture in shaping attitudes toward money. Different societies view wealth through distinct lenses, influenced by history, religion, and socioeconomic structures. For instance, Western cultures often emphasize individual achievement and material success, whereas many Eastern philosophies advocate simplicity and contentment.

Religion plays a particularly significant role in framing ethical perspectives on money. Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism all address issues of greed, charity, and stewardship. Islamic finance prohibits interest (riba), promoting shared risk and ethical investments. Buddhist teachings encourage detachment from material desires, advocating mindfulness and generosity. These principles challenge conventional notions of wealth accumulation, offering alternative frameworks for understanding prosperity.

Globalization has blurred traditional boundaries, creating hybrid attitudes toward money. Younger generations, shaped by digital innovation and social media, increasingly value experiences over ownership. The rise of cryptocurrencies and decentralized finance reflects a shift toward transparency and autonomy in managing wealth. Such trends highlight the evolving interplay between technology, culture, and psychology in redefining our relationship with money.

Conclusion: Toward a Balanced Relationship with Money

Money is undeniably a double-edged sword—a source of empowerment and liberation, yet also a potential catalyst for greed, inequality, and unhappiness. Its influence on the human mind is profound, shaping everything from basic survival instincts to complex societal structures. To navigate this intricate landscape, we must cultivate awareness of both the benefits and pitfalls of wealth.

Achieving a balanced relationship with money requires integrating psychological insights with practical strategies. Practicing gratitude, setting meaningful goals, and fostering empathy can counteract the corrosive effects of materialism. On a broader scale, addressing systemic inequities and promoting financial education can empower communities to thrive collectively.

Ultimately, money is neither inherently good nor evil—it is a reflection of human values and priorities. By aligning our financial habits with deeper purpose and ethical considerations, we can harness its transformative potential to create a more equitable and fulfilling world. As Aristotle wisely noted, “Wealth is evidently not the good we are seeking; for it is merely useful and for the sake of something else.” Perhaps the true measure of wealth lies not in what we possess, but in how we use it to enrich ourselves and others.